2. User

If you knew something special about the users of your search app, would you design the experience differently?

Yes, you would.

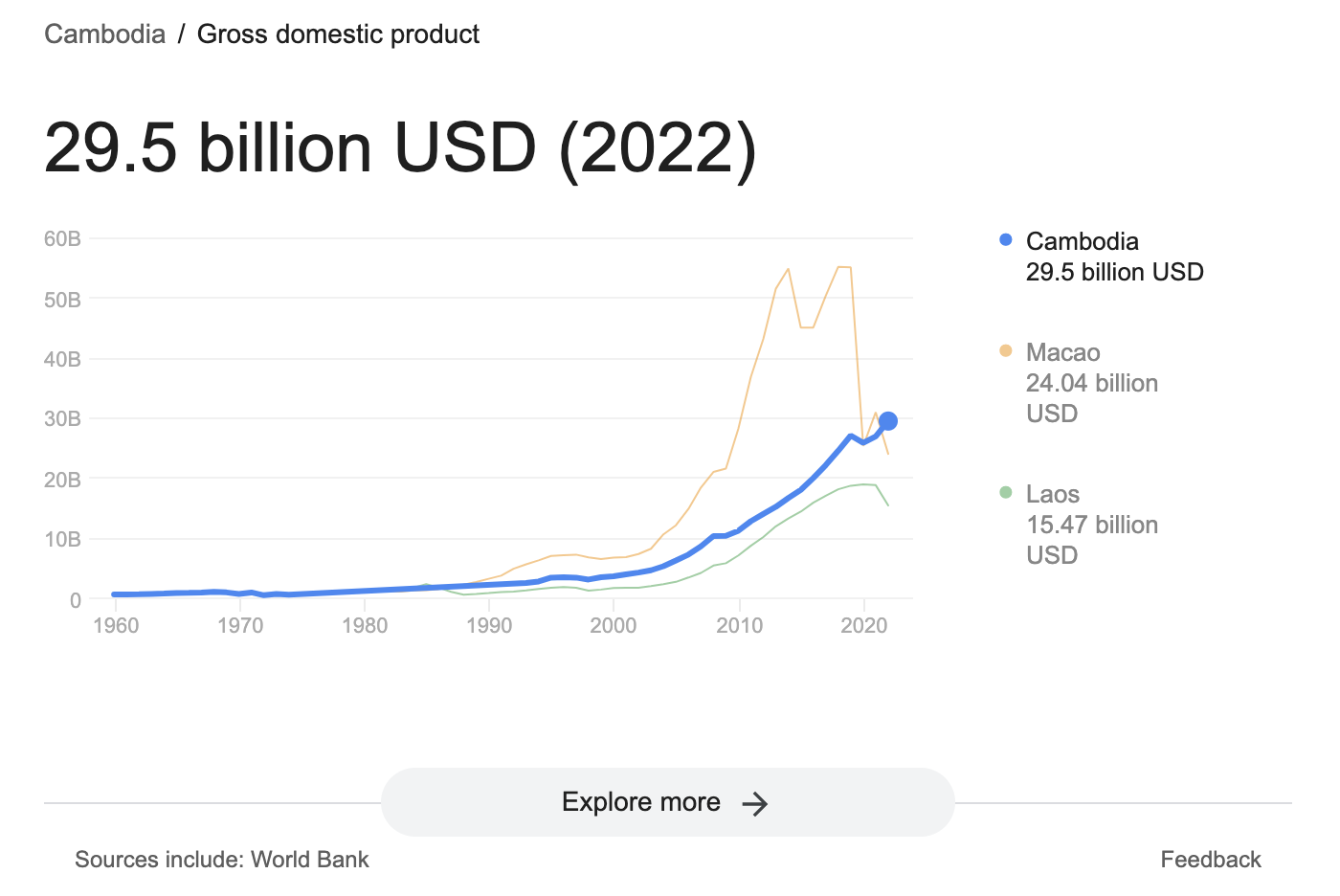

For example, if you know that policymakers who use your search app need data for their work, how would you address a query like, "What is the GDP of Cambodia?" Would you give them links to documents containing the GDP data for Cambodia? Or would you show the GDP data and the answer directly in the results snippet, as Google does?

Google gives a direct answer in response to the query: GDP of Cambodia.

In Designing the Search Experience authors Tony Russell-Rose and Tyler Tate introduce the concept of “search modes” to counter the commonly held assumption that search is just about finding something. They state:

Defining the search problem as one of findability alone is a common misconception. Moreover, it unnecessarily constrains our view and limits opportunities to look beyond information retrieval and on to broader information needs and goals. An online shopper, for example, whose goal is to understand the options available in choosing an affordable home entertainment system, has needs that go far beyond pure findability. And likewise, an engineer, whose goal is to manage the risks associated with component obsolescence, has needs that go far beyond finding information (p. 71-72)

Search modes tell us that users have different requirements when looking for information. They use search to find information and explore, compare, analyse, monitor, etc. This insight is essential to designing compelling search experiences.

There are four common types of search behaviours. Described using character portrayals or personas, these are:

- Assistant

- Explorer

- Analyst

- Executive

Search personas

Assistant

Just the answers.

Examples:

- Do I need a visa to enter Myanmar?

- How many pounds in a kilogram?

- What does this transaction code mean?

Explorer

The breadth and depth of options.

Examples:

- Where do I advertise for Java developers?

- What are the restaurants near me?

- What are my employment benefits?

Analyst

Making the right decision.

Examples:

- Does that company sell ‘fair-trade’ coffee?

- Which is the best phone to buy for Dad?

- How does the Nissan X-Trail compare with other cars in its class?

Executive

Trends and insights.

Examples:

- How have sales fared since the apology for faulty software in our cars?

- How many cases were opened this year, and how many were closed?

- Which areas in Singapore have the highest yield for office rentals?

These personas offer a lens through which you can better understand user needs and behaviours. But first, you must invest time and effort to study your users.

Meeting your users to learn first-hand what they do and why, how they work and the bottlenecks they face will open your mind to ideas that will help design effective search experiences.

After your study, you should be able to answer two crucial questions:

- Is there a dominant search persona at play?

- What are the top search tasks?

A dominant persona emerges when many users exhibit behaviours similar to one of the four personas we described earlier. For example, if you find many users trying to get overviews and trends, you see signs of an 'Executive' persona.

Knowing the dominant persona will help surface the right ideas. Continuing with the 'Executive', they favour dashboards and charts over documents and links.

After you’ve identified the search personas (both dominant and minor), you need to define the top search tasks for each.

A** top search task** is a task that matters a lot to many users. For example, the dominant persona on a bank’s self-support website will typically be an ‘Assistant’—find quick answers. A top search task may be to find the location of the bank’s branches and their operating hours.

A search task embodies a job a user is trying to get done. Searching is not the goal but a means to accomplish a job. The person looking for the ‘GDP of Cambodia’ will perhaps use the data in a slide deck pitched at investors. The job-to-be-done is to get investment, not download the GDP data. Similarly, the job-to-be-done for the person looking at the bank’s operating hours is perhaps to pay for an overseas purchase, not to find the ‘contact us’ page. Knowing the job-to-be-done will help in designing effective search experiences.

Incidentally, the Job-to-be-done, or JTBD for short, is a popular marketing and product development strategy championed by Clayton Christensen, an acclaimed professor at Harvard Business School.

Interviewing users, especially along their decision-making journeys, often identifies the JTBD. The journey reveals the many jobs that users try to complete and how they choose among alternative solutions.

For example, a person looking for GDP data on Cambodia can get the information from several sources, such as journals, databases, or personal contacts. The choice of a particular source reveals the person's criteria for getting the job done. It could be the speed of finding and copying the information into a slide deck.

Once the the job-to-be-done is identified, you can write it down using the form:

- When I…

- I want to…

- So that I can…

For example:

- When I want to pitch to investors

- I want to use data to convince them of market opportunities in Cambodia

- So that I can get financial investment for my project

You can also add some criteria of success, such as:

- Ease of finding the right data

- Ease of making changes to the data

- Ease of copying data to a slide deck

I would like to point out that a study of search persona and their search tasks expressed as JTBD statements will reveal many gaps in the quality of the available content.

For example, a JTBD may suggest presenting a country’s GDP information as a graph on search result snippets. However, the content may be in data tables inside PDF documents. In this case, the right thing to do is to figure out an automatic way to extract the data table and build the graphs. Yes, this may be a lot of work to do, but creating a culture of designing compelling search experiences is essential.

Next up: designing search interfaces that cater to dominant personas and search tasks.