Lists

Lists are a simple and elegant way of organising low-volume information. We’ve all made lists at some point. We create shopping lists, to-do lists, checklists, and reminder lists without even realizing that we’re using one of the most natural and efficient information organization devices available.

Lists are useful because they group related information, which can be things, concepts or ideas.

A list of things to buy on the next visit to the grocery store:

- Bread

- Eggs

- Cheese

- Tomatoes

- Carrots

- Milk

- Batteries

A list of webpages on planning an official overseas trip:

- Research and planning

- Budget

- Accommodation

- Air transport

- Land transport

- Local contacts

- Emergency numbers

- FAQs

Although lists are easy and effective when you’re the one using it, things can be a little different when you make lists for others. This is because others don’t have the same context and understanding you use when creating the list.

Given below is a list of pages on an intranet that show how to purchase products and services:

- ITT

- ITQ

- <3k

- Reimbursements

- Period

- Outsource

You know precisely what you’re referring to if you've made this list. However, for everybody else, it is a list of unknowns!

If you want to know: ITT is “Invitation to Tender” and ITQ is “Invitation to Quote”.

You might argue that everybody in the company would have the background knowledge to understand the list. This can only be possible if nobody leaves or joins the company and those that stay on come to the same conclusion as you. This is a tall order of shared understanding to ask for.

This brings us to the first principle of making lists: All terms used in a list should pass the common knowledge test.

Common knowledge

Common knowledge is knowledge that is common among a group of people. The group can be small, like people in a project team, or the group can be large, like everyone in the company.

Here are some examples:

- Driving on the left side of the road is common knowledge in Singapore but not in the US.

- Requiring quotes from three different vendors before awarding a project is common knowledge in government agencies but not commercial organisations.

- Using the finance system to make large value purchases and requesting the Admin department to make small value purchases could be common knowledge in one company but not in another.

To repeat, the first principle in making lists: The terms used in a list must be common knowledge to the people using the list.

A corollary would be: Don’t use terms in the list that will make others think.

The list of pages on making purchases shown previously (Version 1) makes people think. A better version would be something like this (see version 2):

Version 1 Purchases

- ITT

- ITQ

- <3k

- Reimbursements

- Period

- Outsource

Version 2 Making purchases

- Making purchases—terms you need to know

- Above 70k – Invitation to Tender

- Below 70k – Initiation to Quote

- Below 3k - Small value

- Below 100 dollars (reimbursements)

- Period contract

- Outsourcing

The list on the right has the following elements:

- Organising principle

- Sequence

- Category labels

- List terms

In the following sections, we’ll go through these elements in detail.

Organising principle

The organising principle determines how the terms in the list are grouped. For example, the previous list on 'Making purchases' is grouped according to the different types of purchases.

Richard Saul Wurman, the author of Information Anxiety, proposed that information could be organised in five different ways:

- Location

- Alphabet (A-Z)

- Time

- Category (subject or topic)

- Hierarchy (continuum or range)

The 5 ways form the acronym LATCH. Let’s consider an example.

Let’s say I want to organise a set of trip reports. Here are the different ways I can do this using LATCH.

Location

Since trips are made to different locations, I could group trip reports by the different locations they were made to.

- Trips made to Asia

- Trips made to US & Canada

- Trips made to Europe

By Alphabet (A-Z)

Trip reports have a name, so I can use that to group all trip reports by alphabet.

- A1 trip report

- A2 trip report

- B1 trip report

- B2 trip report

- ...

By Time

Trips are made at different times, so I can group them by the year they were made.

- Trips made in 2020

- Trips made in 2021

- Trips made in 2022

- Trips made in 2023

By Category (subject or topic)

Trips are made for different reasons, such as research and study or conferences, so that I can group them by these reasons or categories. Grouping by categories is the most common type of organisation.

- Trips made for research and study

- Trips made for joint visits

- Trips made for conferences

By Hierarchy (continuum or range)

When Wurman suggested this way of grouping, he was referring to the range of a particular variable, such as the cost of the trip. I could, for example, group my trip reports based on how much they cost the company. People auditing the company's finances will find such a grouping very useful!

- Less than $5000

- $5000-$10,000

- More than $10,000

There you have it: five different ways of organising trip reports. But are there only five ways of organising information? Not quite. We could add a few more: by audience and by task.

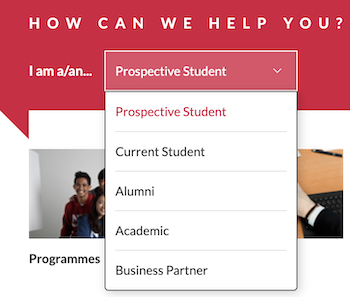

Most education websites have an organisation around their audiences, as shown below.

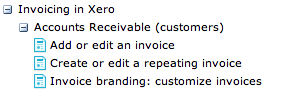

The help section in Xero, an online accounting application, is organised by task.

Organising and meaning

Going back to trip reports, did you notice that each way of organising gave trip reports a specific view and meaning? Organising by location gave a view and meaning that organising by budget did not.

So, which way of organising is better? This depends on why you are organising and for whom. If you were organising trip reports for a finance officer in charge of budgets, then organising by hierarchy (by cost range) may work.

Tony Pritchard describes such a search for meaning in organising the names in The Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, DC. Organising the names alphabetically would depersonalise the lives of the soldiers. Organising by rank (category) would have the same outcome. The authorities, therefore, decided to organise the names of the soldiers based on those they died with. As Pritchard says, “Any other organisation would have altered the meaning and form of the memorial”.

Let’s move on to Sequence.

Sequence

You must have guessed this. A sequence is the order in which the terms appear in the list.

Here is a simple two-step technique you can use to determine the sequence.

- Check if there is an inherent logical sequence. For example:

- Latest on top (by date)

- First to last

- Frequently to occasionally

- Simple to complex

- Known to unknown

- If you can’t find an inherent sequence, go for alphabetical (A-Z) sequencing

If you think there is a structure, and you can’t pick a winner, do a card-sorting test (see the chapter on Card Sorting).

Category labels

After considering the organising principle and the sequence of terms, it’s time to give the list a good category label. Without a label, nothing holds the list together. For example, a list of documents does not mean much unless you give it a label, such as 'trip reports'.

Let’s consider an example.

In the list below, Broccoli belongs to the Vegetables category.

Vegetables

- Broccoli

- Carrots

- Cauliflower

Each term in the list has the same relationship to the category label—they are all veggies. If I add ‘banana’ to the list, the relationship will break—it’s a fruit, not a vegetable.

This is not a revelation—we’re exposed to this kind of stuff as kids. Remember the activity called ‘Pick the odd one out’?

Let’s take a look at the Vegetables category again. If I change the category label to A healthy diet, then bananas can be on the list. The relationship is now correct and intuitive.

A healthy diet

- Bananas

- Broccoli

- Carrots

- Fish

- ...

Some categories are so common that we know exactly what they contain, such as the Vegetables or Pop Music categories. But will people know what exactly goes under the Trip reports category?

This gives us another principle of categories: like the terms in a list, categories are also subject to common knowledge. Trip reports may seem out of place if staff seldom go on trips or don’t write trip reports.

Let’s assume that category trip reports pass the common knowledge test. But is the name the best we can come up with? Or are there better ways of naming categories?

As with everything else, some guidelines and principles can help us.

Good category labels:

- Clearly describe the terms in the list • use simple everyday words

- Use verbs where possible

- Are concise

Web writing expert Ginny Redish lists three types of labels:

| Type of label | What it is | Example | Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question | A label in the form of a question | How do I plan an overseas trip? | Narrow |

| Statement | A label that uses a noun and a verb | Planning an overseas trip | Broad |

| Topic | A label that is a word or short phrase | Overseas trips | Broader |

The Question and Statement types work well on websites and intranets. This does not mean that you should avoid using Topic type. On the contrary, topical names will work quite well if the terms in the list are familiar to your group.

Here are some category labels used for listing staff benefits:

- Medical

- Dental

- Insurance

What does all this mean? Before creating lists for others to use, we need to consider the common knowledge effect. When in doubt, do a card-sorting test (see chapter on Card Sorting).

List terms

Now that we've covered Lists and the importance of Category labels, we can turn our attention to the terms that make up the list itself.

The terms in a list denote action. For example, when going through a grocery list, each term is an item you must buy. When you come across a list in the digital space, it usually is a link to another page or document. In other words, a navigational list.

Since the terms are links to webpages and documents, we are really talking about the naming convention of these items.

Let's consider an example:

| Excellent service award | Excellent service award | Excellent service award |

|---|---|---|

| - What is it? - Who is eligible? - How to apply? - Who has won this before? |

- About the award - Check if you are eligible - Submit your application - View gallery of past winners |

- Award - Eligibility - Application - Past winners |

Did you notice that the terms under a category are the same type?

The terms do not change from a Question type to a Topic type. This is called parallelism. When naming terms, try to keep to one type. Using different types confuses people.

Here is the same list using different types.

- Excellent service award

- What is it?

- Checking if you’re eligible

- Application

- Who has won this before?

The list most likely slowed you down a bit because you had to switch between different types.

You are now ready to tackle Trees!